a Tahltan re-telling of a Tahltan story written down over 100 years ago by a non-Tahltan person, 2023

Instructions for how to use this artwork (if you don’t read anything else, please read this):

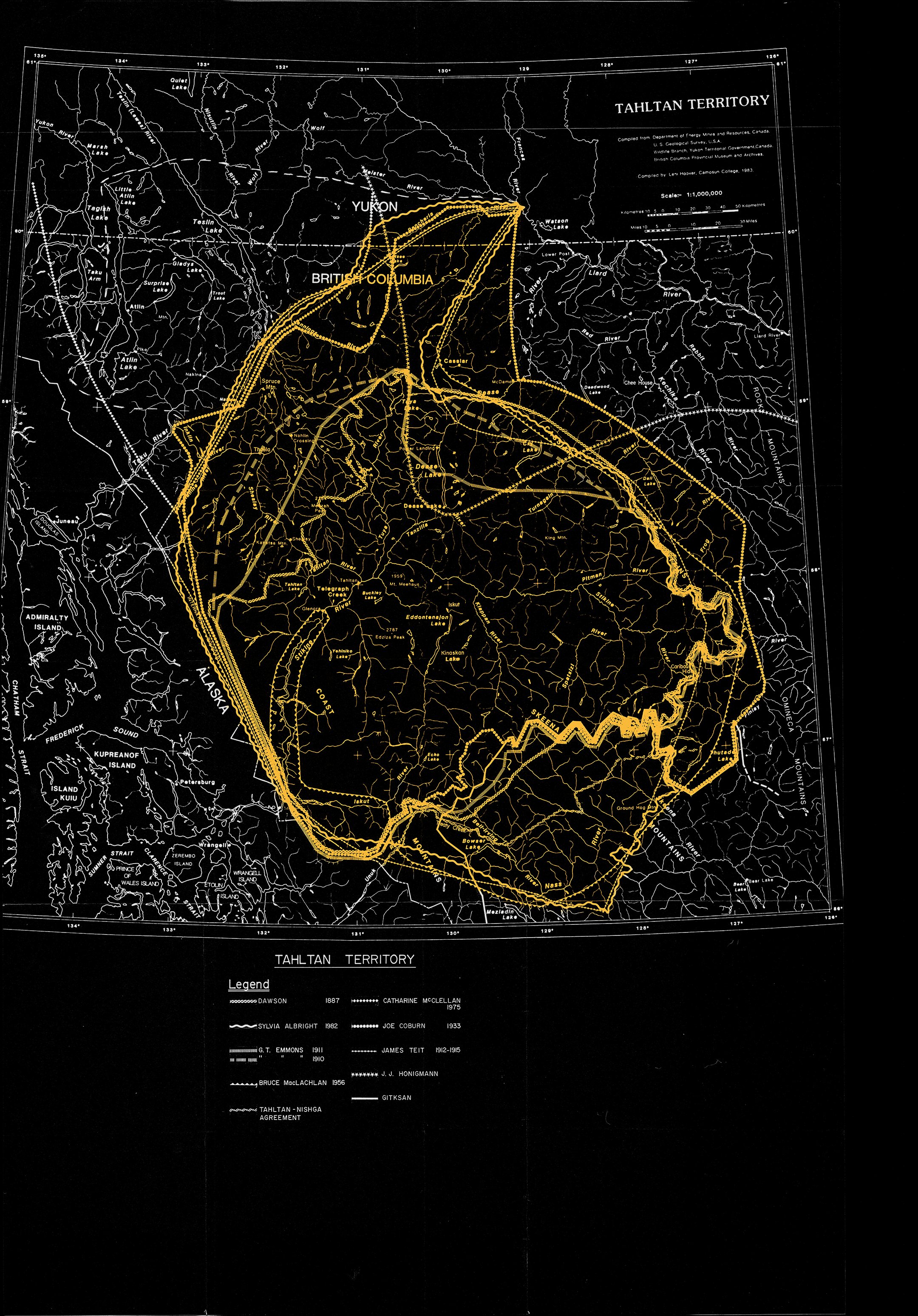

I made these recordings for Tahltan Elders, Tahltan Children, and Tahltan community members so that we might be able to listen to what was written down about our people sometimes over 100 years ago. I made these recordings to honour those original Tahltan Elders and knowledge leaders whose skill and expertise enabled these books to actually be written. I also made these recordings for non-Tahltan listeners, so that they too can listen to what was written down about our Tahltan people sometimes over 100 years ago. I read from these books: The Journals of AJ Stone (1867); The Tahltan Indians by GT Emmons (1911); Tahltan Tales by James Teit (1919); and Northern Athapaskan Art by Kate C. Duncan (1989). I’ve included historical maps of our traditional territory as well. I’ve done this because Tahltan knowledge is centred in Tahltan Territory, and sometimes it helps to see a visual representation of our collective knowledge while you are listening for 100-year old Tahltan knowledge and expertise. These recordings are sequential. They follow the pages of each book. To make the artwork happen, please listen deeply for the Tahltan knowledge that is being purposefully hidden underneath these 100 year-old English words. To make the artwork happen, please imagine each word is like a rain drop falling back into our territory. This artwork is about helping to return what was stolen away from our Territory and our people.

I want to tell you about this artwork called Re-Reading Tahltan.

And I want to tell you that this artwork happens to be a website.

Dzenēs Hoti’e

EzekTah didene keh ushyeh

Edlā Edzūdzah uyeh

Ete’e Pierre uyeh

Estsū Dlune Cho uyeh

Ts’eskiye esdāts’ēhi

Estini Tātl’ah, Tlēgōhīn, Łuwechōn nasdē

First

Over the past year, I’ve been working with the incredible folks of AKA Gallery in Saskatchewan on this web-based artwork. They are Tarin Hughes and Derek Sandbeck. And they are magic.

As the artwork progressed, the team expanded to include: Gabrielle Giroux who helped to build this website, José Contreras who helped to engineer the audio recordings, and Isaac King who helped build the animation that you see on the landing page. This animation is called – a Tahltan re-telling of a Tahltan story written down over 100 years ago by a non-Tahltan person.

SECOND

This artwork has a few origin stories. I think it’s important to list some of them here. One of the origin stories happened right at the beginning of the pandemic when we were all asked to stay home for safety. I decided to read out loud, through a series of Facebook live events, those older Tahltan stories that were written down by James Teit in 1911. Parents were at home. The kids were at home. I thought these live-reading events would be a welcome distraction for their days. I thought maybe these public readings could be some salve for the collective stress that we were all feeling. And I wanted to return these Tahltan stories to a Tahltan spoken voice.

Another origin story for this artwork happens in my parent’s trailer in Smithers, B.C. Our Aunty and Uncle were over to visit, and I had just made a fresh round of gluten-free Bannock. We were making jokes and laughing. I can’t remember exactly how we got onto the subject of those older texts written about the Tahltan people. It just somehow emerged in the conversation. I remember saying to Aunty that absolutely nobody wants to read these older texts, written about our people, because they are so boring and filled with misguided information. Only nerds like me want to read these boring books. I’m all jokes all the time. Then, I told Aunty and Uncle that our Elders should know what was written about our people, and that I was going to make recordings of me reading from those older texts for our Tahltan Elders.

Another origin story for this project happened when I am 16 years old. We had just moved away from Smithers to Surrey BC. I was a troubled teen. The upheaval was difficult, and I skipped a lot of high school (like a lot). I would steal money and go to the movie theatre, or I would go to the library and read books. When I did find or steal money, I went to the big theatre in downtown Vancouver. I left the house at the regular ‘school time’. On the days that I couldn’t go to the movies, I would go to the public library and read books on Art and Indigenous history. After a while, I started wondering if there were books written about our Tahltan people. This is when I first encountered the names James Teit and G.T. Emmons. And this is the first time I read Emmon’s book, The Tahltan Indians. It was in Special Collections at the Vancouver Public Library because it was way out of print.

Another origin story for this project starts with an artist residency at AKA gallery. Tarin approached me to do some thinking/making/dreaming work during the pandemic. AKA gifted me with time and space and supported me to dream big. At the time I was interested in developing language to understand the creative choices of our Ancient Tahltan artists.

Third

It feels important to say that this artwork happens to be a website. This artwork prioritizes and acknowledges the deep and significant Indigenous Art/History(s) that have enabled and activated the practices of Art on these territories now known as Canada. I practice and view these Indigenous Art/Histories as the foundation of everything we now call Art. I am not the only one who has this type of thinking and priority. There are many of us.

This artwork acknowledges the deep history of innovation practice by Indigenous Ancestor Artists. These Artists were able to encounter new materials (brought as trade goods) and utilize them to make articulate expressions of Indigenous power. We, you, and I, are the inheritors of their powerful world-building. This is also a reminder of how artwork(s) were made in community, and through collaboration. It’s the idea that it takes a community to raise up a Totem Pole, or it takes a community to embrace an idea, and how that idea will help our collective survival. It’s the acknowledgement that our Artists loved our culture(s) so deeply that they could dream up new artistic expressions. For me, this means that nothing held back our Artists and the powerful ways that they held/hold our culture.

A Note About the Artwork - Re-Reading Tahltan

The artwork is a series of reading performances. I decided to focus on the older texts written about Tahltan people, by non-Tahltan people. For this work, I was drawn towards the journals of AJ Stone from 1867, The Tahltan Indians written down by GT Emmons in 1911, Tahltan Tales written down by James Teit in 1914, and Athaspaskan Art written by Kate C Duncan in 1984. My art/work is focused on the body, and what the body experiences during the physical act of making. I like to think of myself as a Tahltan performance artist. I feel like I learned how to do this by watching Aunty Rosie Dennis. She told the best jokes during her performances. In many of the recorded performances that you will hear on this website, I am making Tahltan comments during the readings. I couldn’t help myself. I couldn’t keep myself quiet. I needed to stick up for our people, and I needed our people to protect me from their English words. Everything I am saying in between reading their English words is raw, right on the surface of my skin, and real for that moment.

How the artwork works

Each listening experience starts with the words – I’m making these recordings for Tahltan Elders, Tahltan Children, and Tahltan community members to listen to. When you are listening, I invite you to listen deeply, fully— so that we might be able to hear the Tahltan knowledge and expertise that often lies hidden underneath English words like these. This was an important intention for each of the recordings.

I want these recorded words to be like weather, returning pieces of stolen Tahltan expertise back to our territory. I want these words to be like rain, that soaks into the territory and returns nourishment to the people and the land. I want these words to be like sunlight, like wind, like snow— bringing back to the land something that was taken away.

I’m also imagining (hoping for) families to listen to these recordings together. I’m also imagining (hoping for) listeners to take these recordings onto the territory itself. I’m also hoping that we, the listeners, can feel the words of those original Tahltan storytellers and knowledge leaders, because these publications would not exist without their expertise. We can hear our Ancestors speaking. We can hear their expertise because we are living their expertise right now.

As I’ve mentioned, each series of recordings comes from specific books. There are a lot of recordings, actually. Within this artwork that happens to be a website, each series of recordings has its own page. The recordings are sequential, so that you can choose to start where I started reading each of the books. Embedded throughout all of this are Tahltan words, written down, over 100 years ago by non-Tahltan people. These words are spoken out loud by me, and spelled out— for our Tahltan Language warriors. And finally, all of the images that are featured in these non-Tahltan documents are available for visitors to the artwork that happens to be a website. You can drag and drop them onto your personal devices. Each webpage is organized around a historic boundary map of our Tahltan Territory. Each map is gold because our knowledge is the most important gold.

A personal note about the artwork

This might be the most vulnerable artwork I’ve ever made. I didn’t realize how much these reading performances would hurt. Until I read these words out loud, specifically to Tahltan Elders/Children/Community members, I didn’t realize the culture of silence that sits around these types of English words. These English words sit silently inside of 100-year-old structures, and sitting inside of those untouched structures protects those English words, and the ‘ideas’ that they hold on to so desperately. It was hard to read these English words out loud, because they are very specific and designed to make the history of our knowledge(s) disappear.

Now, because these words are protected by historical silences, I feel vulnerable because my own words, spoken in-between their words, are raw— they are on the surface of my body, and aren’t as careful as I would have liked. So many of us have developed our own strategies for speaking back, because we have had to. Those strategies are based on care, and being careful. Reading their words out loud also helped me to experience the Tahltan value systems that stood at odds with their historical and imposed views. Reading their English words out loud helped me to realize that my spoken voice became an echo of those original Tahltan storytellers/knowledge leaders. Listening helped me to hear our Tahltan value systems.

In the Emmons text:

I was reading about how the Tahltan people took slaves. It was the way that this slavery was described that made my head explode a bit. He wrote that our Ancestors took slaves, but also how those captives usually become active contributors to the community. My head exploded again when I realized that Emmons came from a culture that benefitted from the exploitation of enslaved African peoples. He was writing what he knew or had witnessed in his culture and imposing those views/values on top of our culture(s). The owning of slaves by the Western/European cultures was still very active in their being. Canada ended slavery in the 1800s. The United States ended Slavery in 1865. The first enslaved African people were forced to touch down in these territories now known as Canada in 1862, and in The United States in 1619. It’s also important to be clear that we are talking about Chattel Slavery. This means that people were stolen from their homes/territories, and sold as property. It’s also important to acknowledge that part of this was written down on Juneteenth – June 19th. This day acknowledges the emancipation of Black folks from slavery. The official date is June 19, 1865. Two years after the emancipation proclamation. And let’s not forget that Canada and The United States followed up emancipation with over 100 years of segregation. The description from the Emmons book about Slavery was at odds with Tahltan worldview/ ontology because our system made a space for these folks to become part of our community, a part of our families, and active contributors to our cultural systems/structures.

Also from the Emmons text:

The conclusion that non-Indigenous writers often come to texts like these, is how young daughters were sold and were the property of their parents. Once again, this is a value system, rooted in European histories, being imposed overtop of Indigenous systems rooted in these territories. Emmons described daughters being the property of their Fathers, and how their Fathers would sell their daughters in marriage. There is also something about reading these structures out loud and feeling incredibly robbed by them. It’s funny to admit, but I didn’t realize how much these written structures are reified by the historical silence(s) that surround them. We tell ourselves that this was 100 years ago— things have changed now; and we say this to ourselves, knowing how much work we’ve done to be free of these structures. I’ve been taught to trust those English words, to rely on their ‘apparent’ expertise, to help guide my silent reading. It’s a lot to admit, and luckily I have the power to change.

From the Stone recordings:

The final part of the last recording was tough to get through. It wasn’t a lot of pages to read out loud. It was difficult because of when it was written down. It was difficult because of Stone’s opinions about our people. It was difficult because he didn’t seem to care that our people had just survived two pandemics. I don’t know why I wanted to trust him so badly. What made it really difficult was he wrote that an Indian Residential School would save our people. *And for this reason, I would recommend not listening to the last Stone recording until you are ready. It was hard to read out loud. I almost stopped reading because we know how much damage Indian Residential schools did to our people. His belief that our people needed this ‘school’ was too difficult. But I didn’t stop reading out loud because I had made an agreement to read everything.

I want to end this super long artist statement by listing some of the things I’ve learned making this artwork.

Tahltan Knowledge kept me safe while reading these difficult English words.

You CAN hear the Tahltan Knowledge/Expertise that is hidden underneath English words like these.

You CAN feel the Tahltan Knowledge/Expertise that is hidden underneath English words like these.

You CAN hear the older Tahltan Storytellers/Knowledge leaders’ words underneath these English words.

There are many books, written about Indigenous Nations, that are built around these old ideas that hide in their ‘historic’ silence, when you read these types of old English words out loud it means that they can’t hide anymore.

We have to keep reminding ourselves that these old ideas about our people(s) still affect us.

Stone, Emmons, Teit, and Duncan’s books are all indebted to Tahltan's knowledge and expertise. They would have no book without our Elders and Knowledge leaders.

Stone, Emmons, Teit, and Duncan’s books are all interconnected. These authors read these books before writing their books.

Our Tahltan knowledge has been in print since before 1867.

We need to think about these older Western/European value systems and how they shaped these ‘older books’ as evidence of that older culture dying away.

Reading these books out loud for Tahltan Elders/Children/Community members has taught me again of how our past/futures are intimately connected to the experiences of Black, Asian, South Asian, Indian, and Global Indigenous (Racialized People of Colour) people here on these territories now known as Canada.

Reading these books written about Tahltan people by non-Tahltan people over 100 years ago has taught me that we need to do more work honouring and lifting up the experience(s) of Racialized People(s) on Turtle Island who have lived through, and with, these imposed values attempting to silence their cultural expertise and experiences.

When you are reading books like these out loud, read them to someone you love or imagine you are reading out loud to someone you love. This will help you move through the book’s violence(s) mostly unscathed.

Indigenous reading out loud means that you are actually hearing the writer’s spoken voice, the writer’s actual voice. You are hearing their value systems, you are hearing how these value systems are guiding their words and conclusions about us. When you are reading books like these out loud, don’t forget to make a space for your voice to speak back to their voice. When you are reading books like these out loud, don’t forget to make space for the original Storytellers/Knowledge leaders whose expertise helped to bring those books into being.

You will hear the original Storytellers/Knowledge Leaders, and their original words because we are living their skill/expertise every day. You will hear something that sounds familiar.

Indigenous knowledge is fluid and builds experience within physical spaces. This is more powerful than their colonization.

Family, Friends, if you’ve made it to the end of this super-long artist statement. I am grateful. I’m still learning here as an artist and human being and sharing these thoughts with you (hopefully) will help you come into this artwork in powerful ways.

To all of the Tahltan Elders/Children/Community members who are listening to these recorded reading performances, I hope I made enough jokes to make you laugh. And I hope that there is something useful here for you to take away and share with your families.

Medūh, Sogha Sin’lah,

EzekTah (Peter Morin)